Painting the volcanic crags and swirling seas of St Kilda is not a job for the easily discouraged. The archipelago, famously abandoned in 1930 by its inhabitants, is only accessible on days when gales don’t force the helicopter to cancel the sixty-mile flight over the Atlantic. Allan MacDonald eventually made it across, carrying eight canvas boards and his paints. Now he’s brought them back, and more besides.

First View, St Kilda is exactly that: an impression of the spot where the helicopter touches down. Here, MacDonald worked on the first of the boards he had lugged with him. Windswept, drizzly conditions have turned the sea monochrome and the air misty; the entire painting, apart from some subtle flecks of yellow in the surf and some barely perceptible reds and greens in the distant mountains, is rendered in muted tones of blue. It’s an unmistakable MacDonald picture: confident, highly textured, urgent, devoid of any prissiness or pretension. And, as in many of his best works, its bleak Northern scenery and predominance of ‘cool’ colours might be expected to add up to a gloomy effect, an emotional oppression to match the threatening weather that so often gathers in the frame – yet somehow the opposite happens. These pictures lift our spirits and glow with excitement.

Allan MacDonald is determined to resist this taming process. His canvases refuse to settle down: they retain their urgency, their sense of being an excited dispatch from remote places. Let me try to show you the amazing things I’ve just seen, they seem to say. Yet it would be a mistake to ascribe this freshness wholly to a conscious avoidance of formula, as though MacDonald’s main concern were to keep his artistic principles undiluted. There is a deeper reason, which only becomes evident in conversation with him. Again and again, he speaks of the awe that nature inspires in him; whenever he is praised for achieving certain effects, he shifts the conversation back to the physical place he was privileged to witness, the light, the behaviour of seawater and so on. “I believe in a created world,” he says. “I don’t believe it came from nothing.” This is more than a statement of personal faith; it is a questioning of the notion that artists can create new realities. When faced with a sun setting behind a St Kilda cliff, you can daub some paint on a canvas and try to capture a “tiny wee echo”, but “you can’t take much credit. I’m not that clever.” In judging his achievements so humbly, MacDonald underestimates his own interpretative gifts. His best pictures are much more than echoes of a superior natural reality; they are highly personal, and powerful in a different way from the phenomena that inspired them. It is this tension – between the worshipful reluctance to falsify and the artistic instinct to create freely – that makes MacDonald’s art so interesting.

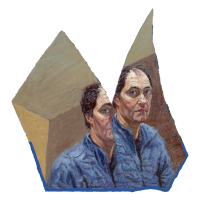

The fact that MacDonald’s work has not yet lapsed into formula is all the more remarkable given the factors that have remained constant over the years. He still lives in the same place in Ross-shire. His studio is still a cramped wooden shed; his preferred painting environment remains outside, in all weathers. He still pursues a vision that could be called Northern European Expressionist, employing thick impasto and dramatic tonal contrasts. He still uses up enough extra-large tubes of Ultramarine Blue and Titanium White to keep half the Highlands’ arts supplies stores in business. His technique still depends on a curious fusion of recklessness and care: the canvas is initially “attacked” (MacDonald’s own term) with a fully-loaded brush, in the hope of capturing something mysterious; later the results are assessed, finessed, reworked. It’s a modus operandi that allows technique to improve without sacrificing risk or adventure.

The four largest pictures, seen together, offer a panoramic view of St Kilda. Day of Storms, Island of Soay and Beneath Connichar are particularly impressive, capturing the monumental solidity of the mountains, the changeable skies and the constant swirl of the Atlantic Ocean. So convincing are these images – not in a narrow photographic sense, but in the sense of communicating the sensual reality of the place – that it’s tempting to conclude that we are being offered direct access to the scene. This is illusory, of course; MacDonald’s St Kilda is a highly personal vision, mediated through his own spirit. In many of his pictures, he is striving to express the same idea: a balance between serenity and turmoil, permanence and flux.

Winter Storm was completed in an hour and a half. It is one of several evocations of a phenomenon that fascinates MacDonald: the crash of waves against the shore (flux versus permanence again). MacDonald eschews… literalism and allows the sea its formless energy. In Winter Storm, as in the other cliff face pictures, the sheer impact of water against rock is palpable. This illusion of ceaseless movement is achieved with abstract clots and swirls, which the viewer’s brain decodes into surging foam or even freewheeling seagulls – it’s all there.

Another challenge which often defeats the best efforts of landscape painters is the sun. MacDonald has said: “In painting the sun, you’re always on a loser: you’re painting something that, in reality, can’t be looked at.” In past works, MacDonald has tried to do justice to this visual overload with supernaturally blazing suns, thick whorls of yellow that seemed to have been squeezed directly out of the tube. In his newer paintings, he tackles the paradox a different way: by letting nature obscure and veil the light source. Beneath Connichar chooses a moment when the sun is hidden behind a towering volcanic crag; the refracted glow of it transforms the sky and the islands. In Day of Storms, the sun is diffused through a haze of threatening rain, yet still manages to brighten everything. In Island of Soay, a bank of cloud descends, obliterating the upper reaches of the landscape, yet the sun incandesces through the murk, casting golden yellow highlights on the dark ocean. In Island of Don, the sun is an amorphous wildfire in the gloomy cloudscape, a weirdly dispersed spill of light that leaks from sky straight into sea. In Of Cliffs and Caves, the sun retains its orb shape but is tucked at the extreme edge of the composition, as if to acknowledge the eye’s inability to look at it directly; it trails a syrupy slick of light onto the land.

Where to next for Allan MacDonald? He singles out the almost wholly abstract Strathfarrar as one of his favourites: “I think that’s the direction my work’s going to go.” Strathfarrar, along with Light Moment, South Uist and Summer Evening, are essentially studies in light, disconnected from the context of specific, recognisable place. However, I suspect that MacDonald will never abandon those specifics entirely. His attachment to landscape is too strong, his enthusiasm for particular locales too intense. The abstraction of Strathfarrar arises from the physical world but has ceased to be physical; it no longer needs the world. Its universe is implicitly internal, and once the artist accepts this, there is no compelling reason ever to leave the studio. MacDonald is already pondering the practicalities of transporting larger canvases to St Kilda, calculating how much painting gear he can feasibly carry to his next remote destination. He still wants to be out there in the wilderness, and he still wants, through his extraordinary paintings, to take us with him.