It’s a strange world. I’m strange, you are strange, and the person next to you is strange. I mention this because we sometimes have the perception that everything strange is out there. Science Fiction and Fantasy adventures fuel this unease. Orcs, Goblins, Daleks and Dementors do not inhabit the distant universe but in reality live in the outer reaches of our imaginations. Outer space ain’t half as strange as inner space.

No, it’s we who are strange. There is nothing stranger than what you see in the mirror each day, or the birch tree you pass on your way to work, or frost on a spiders web, or the grey haired lady crossing the road with her shopping bag.

In 2022 I took up a Residency on Hrisey, a small island on the tip of Northern Iceland. This body of work grew directly from my stay there. Hrisey is a small flat island cocooned in the long arms of the East and West Fjords; a cold embrace.

From here, on my daily walks around the island, I watched the drama unfold. On the West side, the cemetery and the bell tower, overlooked by a ruined house. The East side, pared of human presence, silent except for spouting whales and the faint white noise of distant shorelines.

I lingered much at the cemetery, with its multifarious white crosses. It’s one of the few places in the landscape where we look back and forward, while standing in the present. Back with a sense of loss and altered memory, but also forward with the resurrection narrative. Whether we believe it or not it’s a reminder that we alone, in the natural world, have this capacity to step outside the here and now.

Cemeteries remind us of the long wait. We are all waiting for something. A better world, Eutopia, Arcadia, the Promised Land, Tir na Og. One ancient writer surmised that eternity is set in the heart of man. Our DNA seems hard wired to look ahead. A lot of my evenings on Hrisey were spent waiting, straining my eyes to see the promised Aurora. The occasional green glow led me on, pulling me out of the warmth on the off chance that the glimmer would become an extravaganza. Then it happened, on the penultimate evening. For a moment, the promise was fulfilled, the waiting over as a riotous explosion of colour and light passed overhead. But the clue is in the last three words; it passed and I was back out the next night waiting again.

At the end of November, half the island squeezed into the red roofed church for Advent, the ultimate season of waiting, then left for the cemetery to the strains of Silent Night. ‘All is bright’ they sang in the pitch darkness. ‘Glories stream from heaven afar’ as a faint green geomagnetic wave hovered overhead.

On the East side, a small sign notified me that the large mountain opposite, Mt Kaldbakur, was a renowned Fountain of energy. It suggested that if I lingered there, I would find peace within my soul, that my ‘inner eye’ would perceive all sorts of mysteries. But all energy has a source, and therein lies my interest. Inanimate matter (Mt Kaldbakur) has no soul, no ‘inner eye’, no ability to look back or project forward. The Fountain is elsewhere.

Halfway through my stay, I headed South to meet up with my family and encounter other wonders. The black waves of Rekynisfara, the great outpouring of Selfloss waterfall, and the sea moulded ice sculptures of Diamond Beach.

The latter arrive on the Jokulsarlon shoreline, sea jewels almost immaculate in their conception. No Ming vase or Henry Moore sculpture could approach their perfection, and they appear as a surprising gift, as does all nature. In the fading light, we stopped at Svinnfellsjokull glacier, it’s remorseless cold weight belying the reality that it is vanishing.

Amidst such peculiarities, a thought presented itself: what on (this strange) earth am I going to do with all this?

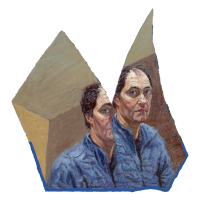

My work was to garner all these different elements together, put them in the mixer, add a large helping of intuition and end up with a cohesive body of work. A process not unlike the way the ice sculptures reached their destination, pushed, pulled and moulded, changed.

The final collection of paintings is a bit of everything above. They are paintings of Iceland and they are not paintings of Iceland. There is no agenda or cause, no cultural comment, no desire to revel in the ugliness of things. But there is a sense of something big out there, lurking just beneath the surface. Occasionally, it breaks through, but you might have to wait. And while we wait, let our strangeness and that of our surroundings indwell us, for landscape is also an interior reality, not just an exterior one.

Star Trek uses the line ‘Space, the final frontier’ but this is deceptive. Our final frontier is the one between the here and now and the hereafter. This fertile ground is strangely neglected in contemporary Art (though Gustav Mahler certainly referenced it in his ‘Resurrection’ symphony).

Below the snowline, the shadowed earth stretches out, while above is a dazzling exalted whiteness. Mortality is either the final plunge or lift off. The glimmer is a dying ember or a precursor to an unimaginable extravaganza.

Exhibition at Brown’s Gallery Inverness, June the 15 th 2024