Catalogue introduction by Allan MacDonald | Moment in the Sun

Where did this begin? Partly in 2019, when I was awarded the Balavoulin Art Grant, but really over 25 years ago when a friend returned home from Canada with a book called Silence and the Storm. Inside were paintings by Tom Thomson, life size reproductions of his small exhilarating paintings.

Something happened: a mechanism that was previously jammed was unlocked. For the first time, despite having lived in the north of Scotland for most of my life, I could see the landscape around me. It wasn’t the road to Damascus, but it was a definitely a road. Thomson didn’t do anything startling, especially in light of his contemporaries in Europe. No new language, like Cubism, no Fauvist insight, no questioning of reality. Against such seismic tremors, the work of Tom Thomson would barely register. What set him apart was his trajectory. David Silcox says: ‘Had he not in his last five years created these panels of magic, his life and death would have passed unnoticed’. Harold Town writes ‘Theirs (Thomson and the Group of seven) was an involution of pivotal national significance precisely because it did not mirror, substantiate, imitate or pay the slightest heed to world art’.

It’s within this framework that I begin to understand my attraction. While the Scottish Colourists upped sticks to the south of France or the exotic sands of Iona, Thomson canoed around Algonquin, transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary.

So I set of for Canada, uncertain what would transpire. I took about thirty small panels with me and a bag of paints. Expectations were low. Painting outdoors is difficult enough on you own doorstep, never mind across the other side of the world.

The first week was dire, but on the third week, I came across Tea Lake Dam. Thomson painted here, immortalised in a black and white photo of him fishing. It was here that I got a foothold. The silence without the storm, high pressure and the fall combining to give a golden stillness. Surrounded, no horizon. Low vantage point, bordering claustrophobic. The outworking of an obsession. But then most art is the outworking of an obsession.

I returned, with a bag full of small paintings, mainly yellow, red, blue and green. Garish you might think. Certainly a challenge to handle such attention-seeking colours. But also with a new respect for what Thomson achieved.

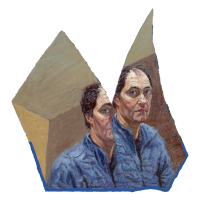

Back in the studio, the body of work grew from the original twenty small panels. It took off at a tangent I hadn’t envisaged. New palette, different energy, a greater design element. The paintings try and embody that stillness we sense before something happens. A sense of approaching, waiting, apprehension, longing.

Last Autumn, I was painting by a river near Eskadale, impossibly still, saturated in orange, green and gold. I heard a splash and looked up expecting to see a fish. Instead, a lady on a paddleboard slipped past wordlessly, blue black against the gold backdrop. Months later, after viewing Arnold Bocklin’s great painting Isles of Death, I recalled this moment and knew it had to be expanded.

In a way, I look on all my paintings as expanded moments. One writer said ‘We do not remember days, just moments’ but some of these moments then need reshaped, edited, singled out, transformed. Above all; they mustn’t stay behind us, but must reappear. And that’s my job really: to turn something fixed into something stretchy; a moment in time into timelessness; something instant into something constant; something defined into something illimitable; what’s before me, into what’s ahead of me.

Which brings us full circle: Ian Dejardin, Executive Director at the McMichael museum near Toronto, suggests that the elevation of the sketch is one of the most significant legacies of Thomson and the Group of Seven. The humble sketch got an upgrade. Something small, quickly executed and immediate became something lasting, valuable in its own right and not a means to an end. Thomson’s ability to distil the vast Canadian wilderness onto a 10”x 8” panel ensured this. Just how much I’ve absorbed this didn’t become apparent until my recent trip to Canada. Even my larger paintings, done on location, are compressed into short bouts of intense activity. Developing that vitality, especially back in the studio, is a challenge that Thomson himself struggled with.

If we pull the lens right back, then the overview has the same pattern. While these paintings try and record the moment, they really aim at something more limitless. German artist Anselm Keifer said ‘Art is longing. You never arrive, but you keep going in the hope that you will’. CS Lewis went further: ‘If we find ourselves with a desire that nothing in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is we were made for another world’.

Returning from the haze and shimmer of Tea Lake Dam, I started developing the small paintings I’d done, and then came Lockdown. Algonquin began to feel like a mirage, a world of freedom and colour suddenly beyond my reach. A distant oasis. The paintings and even the studio became a haven, accentuated by the travel restrictions, and the gold orange glow lingered through a long winter.

Thomson’s early death, on Canoe Lake, appeared to bring his moment in the sun to a premature end. Except that it didn’t. It keeps stretching, propelling forward, a long blue ripple, traceable, heading into the unknown. Keifer might doubt the destination, but rivers always run to the source. We ain’t seen nothing yet.